Concussion

What is a concussion?

According to the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine, a concussion can be defined as “a traumatically induced physiologic disruption of brain function.” Moreover, a sport related concussion is defined as “a traumatic brain injury induced by biomechanical forces.”

What causes a concussion?

Common causes of concussion include falls, motor vehicle accidents, sports, blunt trauma, or assaults which induce diffuse axonal injury from acceleration-deceleration and/or rotational acceleration mechanisms. In other words, the rapid movement of the brain inside the skull causes stretching and damage of tiny nerve fibers that carry signals in the brain which can lead to disruption of communication between different parts of the brain. This is followed by a complex cascade of biomechanical and neurochemical processes which manifest as the signs and symptoms of concussion. Studies have shown that a force approximately 80G may be necessary to induce a concussive blow. Furthermore, angular acceleration forces from side impact to the head appeared to be more likely to cause head injury compared to front, rear, or top of the head impacts.

How is a concussion diagnosed?

In general, diagnostic criteria for a concussion may include:

- A short period of loss of consciousness (30 minutes or less)

- An acute change in mental status while maintaining a Glasgow coma scale (GCS) of 13-15 within 30 minutes of the injury

- Any retro- or anterograde amnesia lasting less than 24 hours

- Transient or persistent neurologic signs or symptoms.

As it pertains to a sports related concussion, diagnostic criteria typically include the following:

- Injury “caused by either a direct blow to the head, face, neck, or elsewhere in the body with an impulsive force transmitted to the head.”

- “Rapid onset of short-lived impairment of neurological function that resolves spontaneously,” though it must be noted that, “in some cases, signs and symptoms evolve over a number of minutes to hours.”

- “Acute clinical signs and symptoms largely reflect a functional disturbance rather than a structural injury and, as such, no abnormality is seen on standard structural neuro imaging studies” such as a CT or MRI of the head.

- May result “in a range of clinical signs and symptoms that may or may not involve loss of consciousness. Resolution of the clinical and cognitive features typically follows a sequential course. However, in some cases symptoms may be prolonged.”

- The signs and symptoms associated with the sport related concussion “cannot be explained by drug, alcohol, or medication use, other injuries, or other comorbidities.”

What are common symptoms of a concussion?

Symptoms associated with a diagnosis of concussion may be categorized in five groups:

- Physical: Headache or “pressure in head,” neck pain, blurred vision, sensitivity to light (photophobia), sensitivity to noise (phonophobia), or ringing in the ear (tinnitus).

- Balance (vestibular): Nausea, vomiting, dizziness, “room spinning” (vertiginous symptoms), or unsteadiness.

- Cognitive: Concentration impairment, memory impairment, slowed cognitive processing, confusion, feeling “in a fog,” or not “feeling ”

- Mood: Fatigue, low energy, increased emotionality, irritability, sadness, nervous, or anxious.

- Sleep: Drowsiness, excessive sleep, or difficulty falling asleep.

What does a concussion evaluation include?

After a thorough history is taken, a detailed physical examination may include evaluation of mental status, cognition, cranial nerves, cervical spine (neck), strength, sensation, reflexes, coordination, balance, and gait (ability to walk).

How is a concussion treated?

Initially, it is important to limit activities to routine daily activities; limit screen time, school, and/or work to a level that does not increase symptoms; avoid alcohol, sleep medications, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aspirin, and opioid pain medications; and to not drive until cleared by a healthcare professional. Also, if there is a notable change in behavior, repeated vomiting, worsening headache, weakness or numbness in arms or legs, double vision, slurred speech, seizures, inability to recognize people or places, or excessive drowsiness, then emergency department evaluation should be sought as soon as possible.

In most cases, after no more than a few days of physical rest and relative cognitive rest, one can begin a graduated return to sport as well as school or work. The natural history of concussion is quite favorable in a high percentage of cases. After the initial concussion, rapid improvement in symptoms is typically noted over the course of several days to a few weeks, with cognition potentially impaired for up to a week with gradual turn to baseline by 1-3 months.

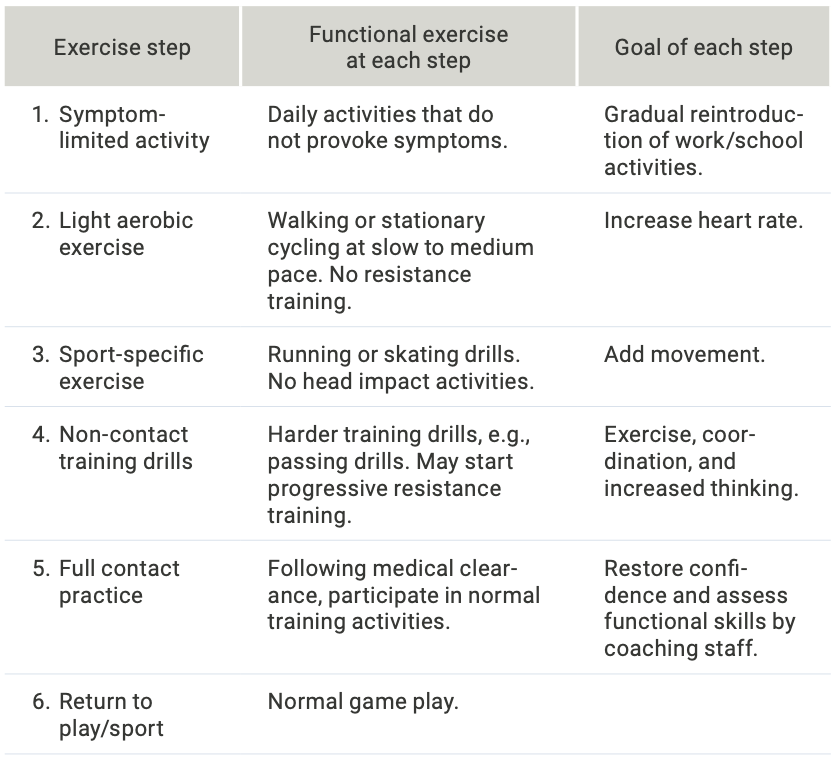

The following is an example of a graduated return to sport:

Typically, each step of the progression lasts 24 hours or longer. It is recommended that, “if any symptoms worsen while exercising, one should return to the previous step in the above series. Resistance training should be added only in the later stages (stage 3 or 4 at the earliest).”

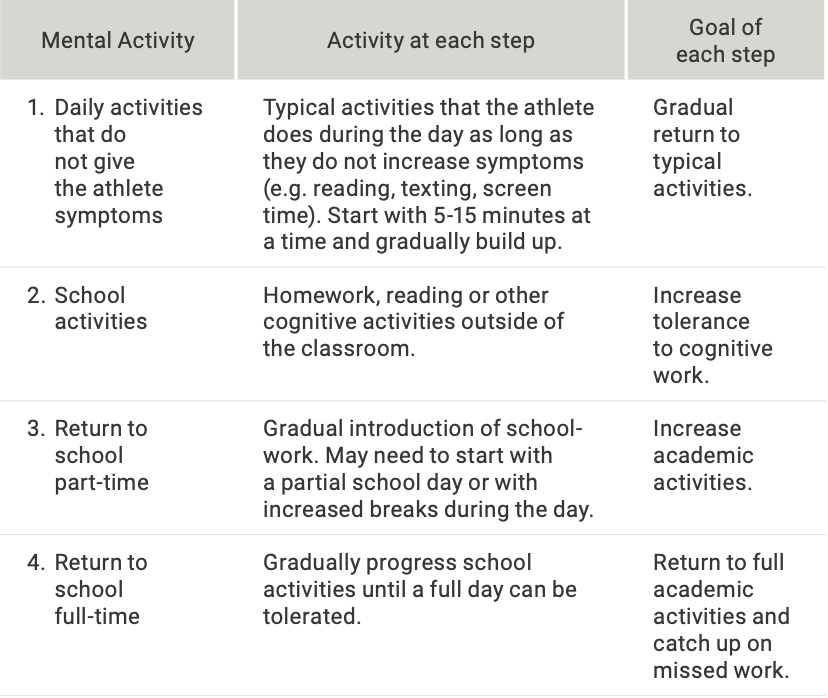

The following is an example of a graduated return to school:

Each concussion is unique and may benefit from an individualized management program. Depending upon the most prominent symptoms, a variety of treatments may be selected. For example, in those with more prominent balance and visual symptoms, vestibular physical therapy may be selected as a primary treatment modality. If memory or concentration are problematic, a neuropsychology evaluation and/or cognitive rehabilitation may be recommended. If headache and/or neck pain are primary contributing factors to once concussion symptoms, there are many treatment options available (see headache and cervical spine sections). In general, in addition to following a graduated return to sport/physical activity, optimization of sleep and stress management remains paramount in concussion recovery.

Echemendia RJ, Meeuwisse W, McCrory P, et al. The Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5th Edition (SCAT5): Background and rationale British Journal of Sports Medicine 2017;51:848-850.